The Life and Work of Walter Battiss

South African 1906 -1982

Written by Sean O’Toole

A vital figure in the story of twentieth-century South African art, Walter Battiss resists easy classification. An accomplished painter, Battiss was also a brilliant draughtsman, exceptional printmaker and occasional sculptor. He produced murals and tapestries, and also took photographs – a lifelong passion. His photographs illustrate his early self-published books, notably South African Paint Pot (Red Fawn Press, 1940), which features his portraits of Lippy Lipschitz and JH Pierneef. Limpopo (1964), an autobiographical travelogue issued by Irma Stern’s publisher Van Schaik, also draws heavily on his photography.

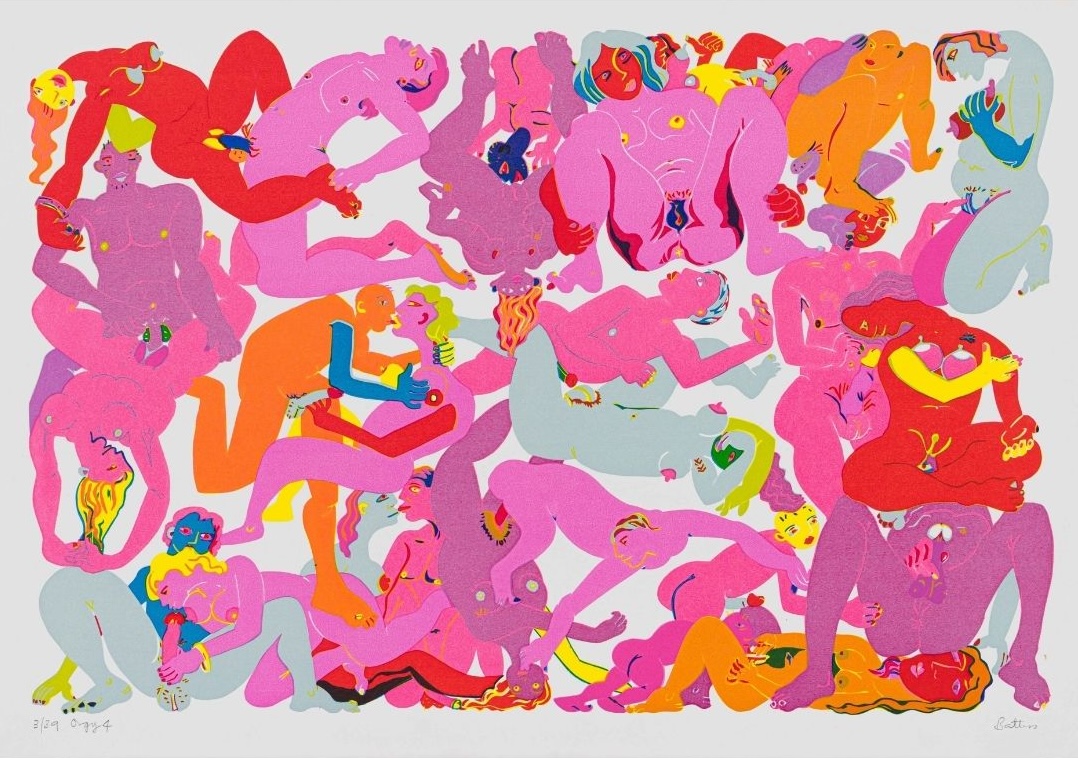

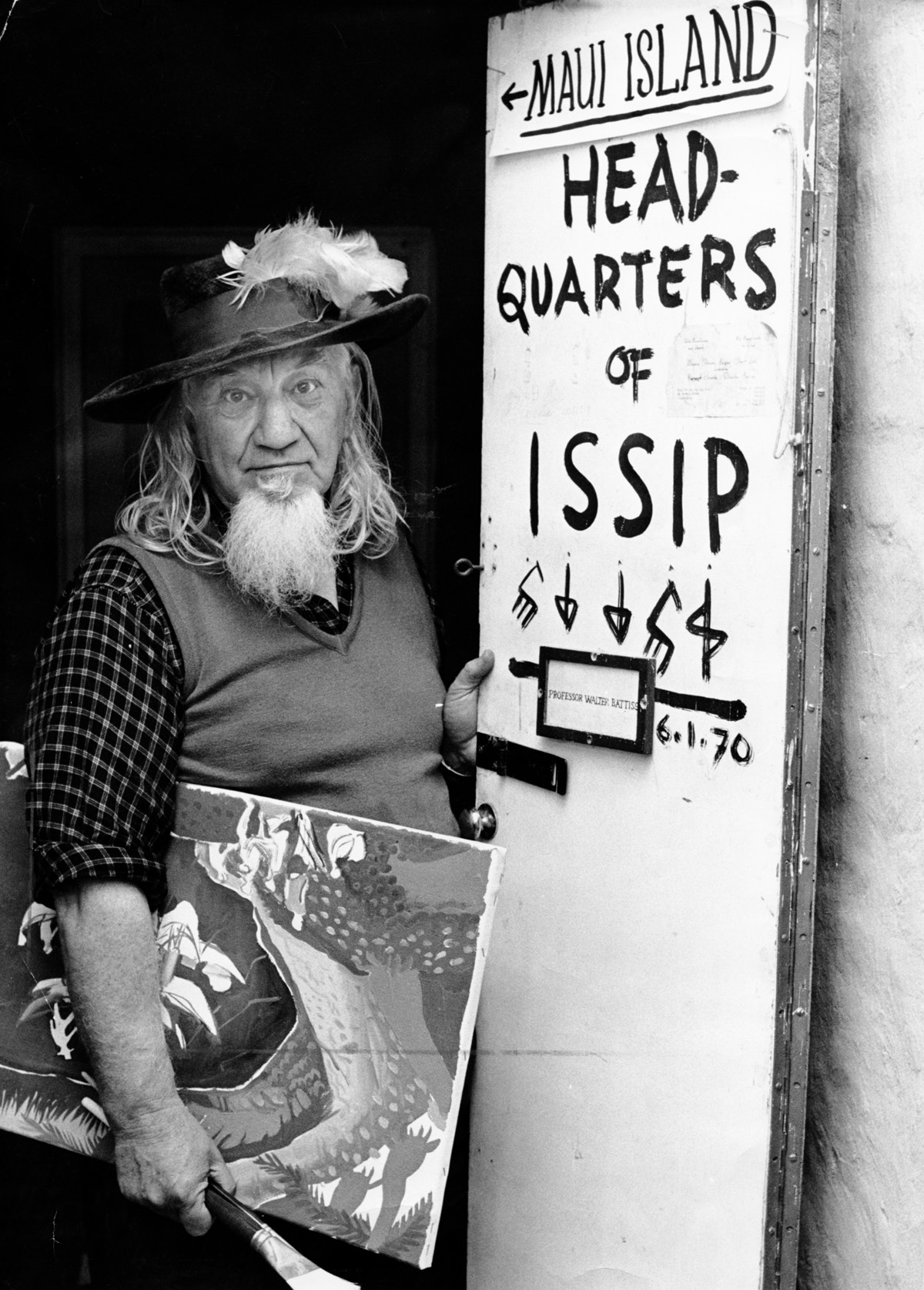

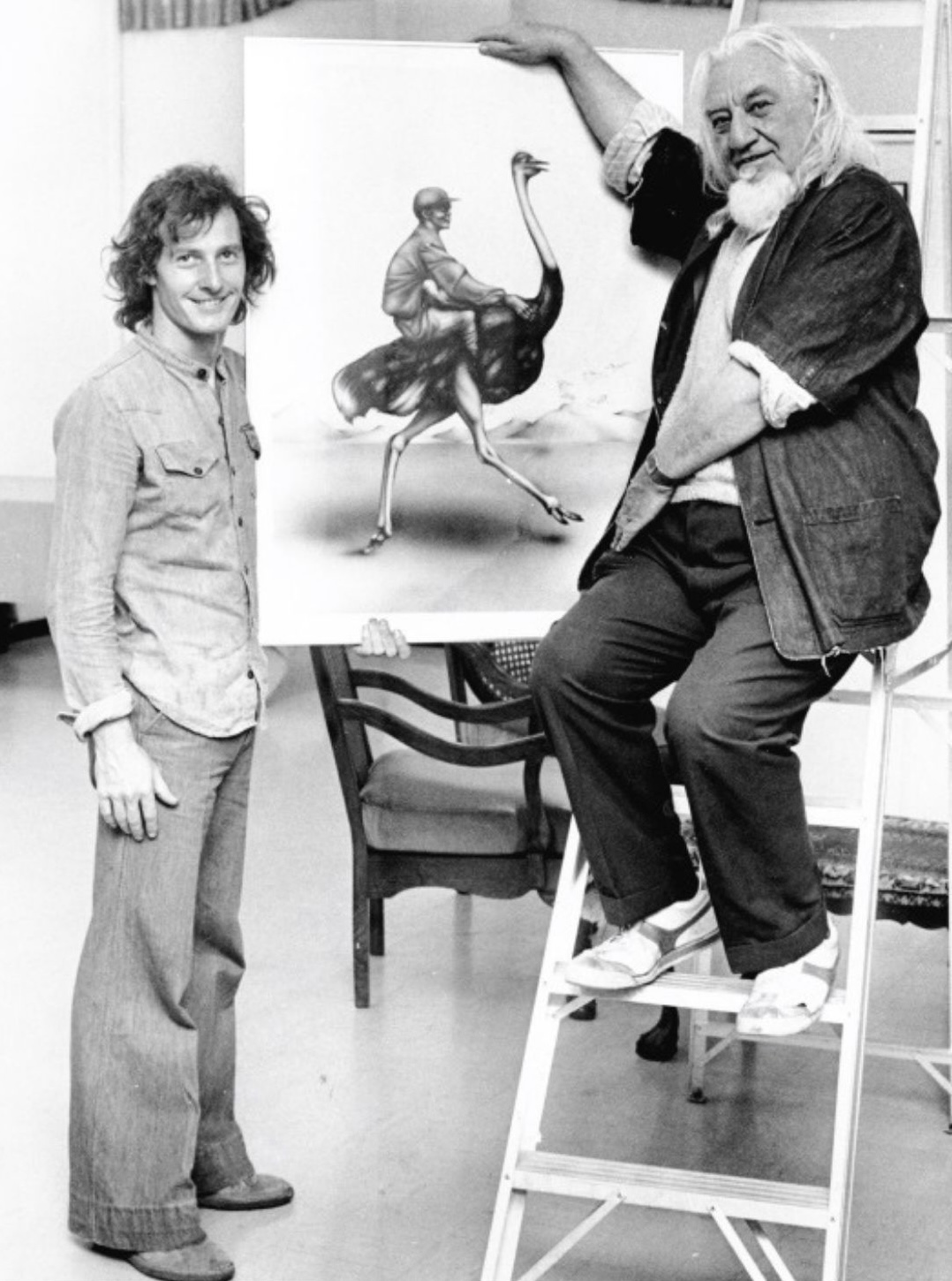

In his later years, after retiring from academia in 1971, Battiss became a seditious pensioner interested in conceptual mischief. In 1973, he invented an imaginary utopia called Fook Island. Inspired by his travels to islands in the Mediterranean and Indian Ocean, Fook’s free-spirited visual expression and democratic ethos were a rebuke to apartheid-era censorship. “Anybody can be king or queen of Fook Island,” he explained. “I am King Ferd the Third, and [his collaborator] Norman Catherine is a Norman King of Fook … People only have to ask.”1

For many, it is this Battiss – the scraggly-haired occupant of a double-storey house in Menlo Park, Pretoria, owner of a Rolls Royce and with a proclivity for nudity, the “gentle anarchist,” as Neville Dubow put it2 — that endures in the imagination. But this is too limiting. Battiss was, if anything, Whitmanesque: “I am large, I contain multitudes.”3 It is worth enumerating those multitudes. Battiss was also a committed visual archaeologist, generous art critic, intermittent poet, much-admired teacher and influential tastemaker. Underpinning all of this was his spirited humanism and optimistic worldview.

What the Fook? The Life and Work of Walter Battiss, the first single-artist auction devoted to Battiss in South Africa, aims to honour the vigorous life force that was Walter Battiss. The catalogue focuses on his oil paintings, watercolours and screenprints from the period 1938 until his death in 1982 – corresponding roughly with his Pretoria years. In 1940, four years into his influential teaching post at Pretoria Boys High School, Battiss moved into a modest home on the eastern periphery of old Pretoria. Its form was inspired by a white house depicted in one of Giotto’s frescoes. Battiss and his wife, Grace, also a painter, lived at “Giotto’s Hill” until their deaths.

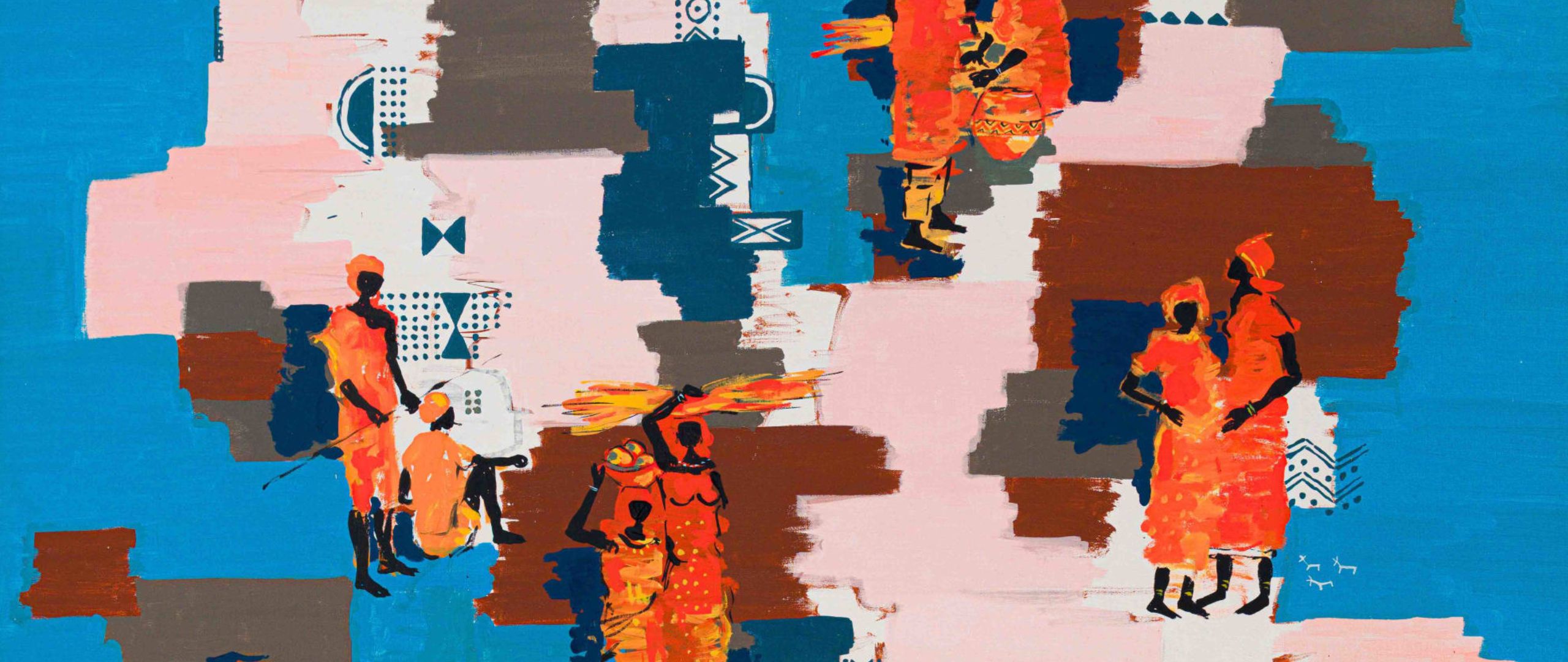

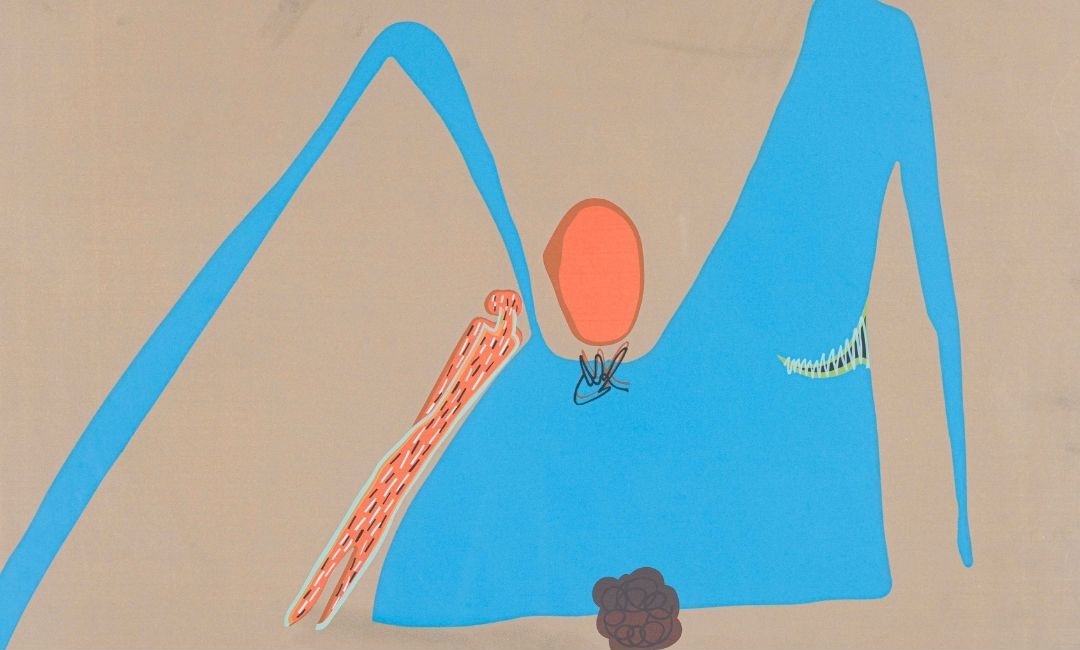

Despite his promiscuous dalliances with various media, Battiss was principally a painter and printmaker. Painting was where he metabolised his romantic ideals and formal his ambitions as an artist interested in human subjects. The catalogue includes important paintings like The Spirit of Africa (c. 1960) (lot XX), an enigmatic figural diptych commissioned for a modernist house in Kimberley. In 1937, Battiss exhibited two abstract works at the Pretoria Music Festival under the pseudonym Gregi Nola. Two undated works, Abstract Palimpsest (lot XX) and Abstract Vortex (lot XX), reveal his aptitude as a non-representational painter.

The catalogue features works from diverse collections, notably those of art historian Murray Schoonraad and renowned composer Robert Schröder. Both were pupils ofBattiss at Pretoria Boys High School (PBHS). Schoonraad became a major authority on Battiss, authoring his 1976 monograph and two other Battiss books. In 1988 he curated an exhibition devoted to the New Group, the reformist-minded collective of painters of which Battiss was a founding member in 1938. Schröder – who composedmusic for over 15,000 commercials and helped launch the careers of Mango Groove and Ringo Madlingozi – spent five decades assembling a personal Battiss collection. Two oils purchased in 1976 for R900 remained the pride of his archive. Other noteworthy pupils of Battiss include artists Walter Westbrook and Malcolm Payne.

The Schoonraad Collection contains important works linked to Battiss’s early biography. In 1933, Battiss discovered the “bigness of South Africa,” as he put it in a letter to Erich Mayer, when he encountered damaged rock paintings on a farm at Malopodraai in the Free State. “I am coming again,” he added.4 Over the next two decades, while teaching at PBHS, Battiss devoted his spare time to finding and documenting rock art across southern Africa. He became a noted authority on both rock engravings (petroglyphs) and rock paintings. He self-published five books on the subject and wrote important articles for The Studio (London, 1948) and Lantern(1951).

Works representative of this early interest include Diepkloof, Rouxville District, Orange Free State (lot XX), a descriptive watercolour from the 1940s detailing a rock painting of eland, and the undated Wartrail, Barkly East C.P. (lot XX), in which he notes “a most surprising grasp of the principles of foreshortening” among rock painters. The Early Men and Women (Cave) (lot XX), a more impressionistic work most likely made in 1938, reflects his break with naturalism following his first visit abroad in the same year. That journey, which included a visit to Paris, prompted a style more directly influenced by southern Africa’s early rock artists.

“It was like a visit to the moon,” Battiss later told painter Larry Scully, who taught at PBHS (1951-65) and wrote his Master’s thesis on the artist. Battiss told Scully that he realised for the first time that “European artists were stealing from Africa the vital forms and colours,” which he had previously ignored. “For Battiss this was probably the most important lesson he was to learn: he must open his mind to everything that contemporary European painting had to offer, and he must open his eyes to the autochthonous forms of the whole of Africa.”5

Battiss’s personal transformation was sincere, and long lasting. He was a lifelong emissary of the new. He consistently championed progressive artists, be it in the form of a glowing promotional blurb for Stern’s artist’s book Congo (1943), or appreciative reviews of Erik Laubscher and Cecil Skotnes. In 1947, he published Alexis Preller’s first monograph. Robert Hodgins was a trainee printer. Braam Kruger painted in the nude with him. And so on. But he didn’t betray seriousness. Battiss was a patron of the short-lived art magazine Fontein (1960), and in 1965, newly installed as an art professor at UNISA, he founded the journal De Arte, still a going concern.

Today, nearly 43 years after Battiss’s passing in 1982, many details of his extraordinary life are slipping from popular memory. Battiss presently inhabits an ambiguous twilight. The durability of an artistic reputation is never guaranteed. Art history reminds us that the careers of Botticelli and El Greco, like many past masters, had to be retrospectively recovered from obscurity. Revival is a slow process – but in the case of Battiss, there are definite milestones.

In the last two decades, Battiss has been the subject of three major exhibitions in Johannesburg: Walter Battiss: Gentle Anarchist (2005) at the Standard Bank Gallery, and the double whammy Walter Battiss: I Invented Myself at the Wits Art Museum, and The Origins of Walter Battiss: Another Curious Palimpsest at the Origins Centre Museum, both in 2016. While not a career retrospective in the museum sense, What the Fook! aims to continue this momentum and honour Battiss, an artist of uncommon significance.

1Jill Johnson (1981) South Africa Speaks, Johannesburg: AD Donker, page 172.

2Neville Dubow, Karin Skawran and Michael Macnamara (eds) (1985) Walter Battiss, Johannesburg: AD Donker, page 93.

3Walt Whitman (1892) Poetry Foundation, Song of Myself (1892), online, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45477/song-of-myself-1892-version, accessed 5 June 2025.

4Neville Dubow, Karin Skawran and Michael Macnamara (eds) (1985) Walter Battiss, Johannesburg: AD Donker, page 40.

5Larry Scully (1963) Walter Battiss, unpublished Master of Arts Dissertation, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, page 23 and 24.

Artist, Walter Battiss

Walter Battiss and Norman Catherine

“What the Fook? celebrates the life and work of Walter Battiss, a protean and prolific figure in the story of twentieth-century South African art. As well as being an important artist, Battiss was an influential teacher, archaeologist, critic and publisher. In 1938 he cofounded the New Group a vibrant collective of burgeoning South African artists united by a shared desire to challenge and transcend the prevailing conservative art conventions of the time. His Fook Island project of the 1970s cemented his status as a boundary-breaking visionary and critic of censorship. His spirit of renewal and optimistic worldview remains deeply resonant today.”

– Leigh Leyde, Head of Sale, Strauss & Co

TALK

Fooking Around: No Man is an Island

with Senior Art Specialist Wilhelm van Rensburg

Saturday, 21 June 2025 at 11am