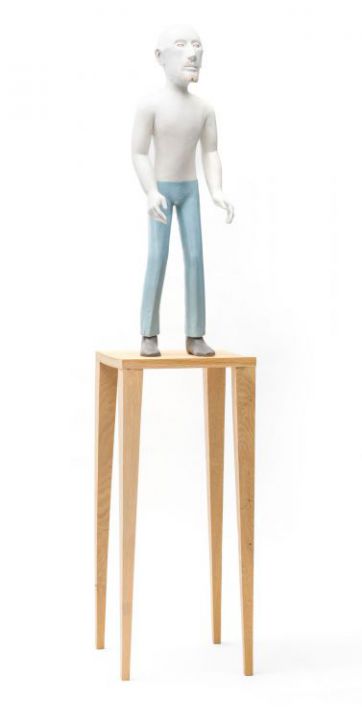

Conrad Botes

Waiting for a Miracle

About this Item

signed and dated 16

Notes

Conrad Botes is best known for his graphic work, which duly received premier billing on the show Impressions from South Africa, 1965 to Now at New York's Museum of Modern Art in 2011. But, alongside this output, Botes has also devoted himself to painting and sculpture. His earliest known sculptural figures date back to 2000 and mimicked the modest scale, graphic simplicity and pop colouration of West African colon figures. By 2008, when Botes held his first solo exhibition with dealer Michael Stevenson, the scale of these painted figures had grown significantly. In a review of this show, art critic Ivor Powell considered the debased Christian iconography that is the wellspring of Botes's art: 'The spiritual stratum that Botes mines is an archaeological and largely decomposed mulch of broken images, holy books and shattered votive statues - the detritus of the imagery of the Christian religion, left over when God died. Its discursive elements - devils, the sacraments of salvation, the conundrums of passion, divinity, and mortality, the mystical narrative of good versus evil - continue to carry an archetypal and visceral charge, a kind of trace memory of their formerly numinous status.'1

The mystical status and supernatural charge of this male figure is, at best, ambiguous. His goatee beard suggests Pan, the pastoral Greek god of the wild, shepherds and flocks. But, unlike Botes's enamel-painted sculpture Sailor (2007), which depicts a similarly expressionless and angular-jawed figure, the man in this lot possesses no horns. Notwithstanding his status as a remaindered god, his alabaster skin links him to other figures in Botes's evolving bestiary, notably White Zombie (2009), a sculpted portrayal of a bald, demon-like figure with white skin and red eyes. The face however bears similarities to Botes's self-portraiture, a recurring constant of his gripping oeuvre, which uses profane references to land lacerating critiques, of self as much as of white society.

1 Ivor Powell (2008). 'Review: Conrad Botes, Satan's Choir at the Gates of Heaven', Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art, No. 22/23, Spring/Summer. Page 192.

Sean O'Toole